Sport at the crossroads: Cricket calling stumps on umpire abuse

This is Part 7 of our ‘Sport at the crossroads’ series, exploring the way different sports codes and associations are tackling the abuse of officials.

Part 1: Football (Soccer)

Part 2: Rugby League

Part 3: Aussie Rules (AFL)

Part 4: Netball

Part 5: Rugby Union

Part 6: Basketball

Part 7: Cricket

Tales from the frontline tackling the abuse of officials – Cricket

Since the original ‘Laws of the Game of Cricket’ were first codified at the Star and Garter pub in Pall Mall in London in 1744, there have been a number of changes to the game.

Scorebooks have replaced notching sticks. Overarm bowling replaced underarm. Six balls are bowled per over instead of 4. Straight bats have replaced curved ones.

The umpires depicted in early paintings look resplendent in long coats, stockings and regal hats, leaning on bats and providing an impartial platform for the game to be played.

“Cricket in Marylebone Fields, 1748” is the earliest known depiction of a cricket match

But some things never change and despite their crucial role, the early umpires were subject to abuse and accusations of bias.

In 1888, Englishman Allan Steel wrote of the plight of umpires in the book ‘Cricket’:

“If anyone were to ask us the question ‘What class of useful men receive most abuse and least thanks for their services?’ we should, without hesitation, reply, ‘Cricket umpires.’”

Fast forward to 2016 and according to a UK study of 763 umpires by the University of Portsmouth, the abuse situation had not improved.

The findings showed that 56% of the mostly recreational umpires had reported verbal abuse every couple of games including aggressive confrontations and 3% had reported physical abuse.

The impact was clear, with over 40% of respondents reporting that abuse was making them question whether or not to continue umpiring.

As a result of the survey and other research and trials conducted by the official law makers at the Marylebone Cricket Club, an adjustment to Law 42 was made which now gives umpires new power in on-field sanctions including, in extreme cases of physical abuse, the right to remove offending players from the field for the rest of the match.

A long history of law making at he Marylebone Cricket Club Picture: medium.com

**

The practice of umpire abuse travelled with Great Britain’s colonial expansion to Australia and in 1843 the Sydney Morning Herald reported on a match between Parramatta and Liverpool and that although Parramatta won: “… the Liverpool men complain of unfair play on the part of the Parramatta men, who it appears, acted in opposition to the decision of their own chosen umpire.”

In 1857 the Sydney Morning Herald reported on a match between the Marylebone Cricket Club and Union Cricket Club which noted: “Some unpleasantness took place during the play in consequence of the decision of one of the umpires.”

In the modern era, the role of the umpire has remained largely the same, notwithstanding the introduction of technology and player challenges at the elite level.

Whilst it is still considered a ‘gentleman’s sport’ by some, there has been a slow decline in the ‘Spirit of Cricket’, a sportsmanlike approach to the game that is encoded in the Laws which includes the following:

‘Respect is central to the Spirit of Cricket, which includes the basic tenets of respecting opponents and the authority of umpires, accepting the umpires’ decisions, showing self-discipline and creating a positive atmosphere through your conduct.’

With a strong Code of Conduct governing the elite game in Australia, including penalties for dissent and verbal abuse, there is a natural expectation that the number of incidents would decrease.

In fact, poor on field behaviour has increased and a more adversarial than collegiate approach often prevails.

Finding an advantage through sledging or ‘mental disintegration’ is common place in modern cricket. Picture: @Cricket Australia

**

By 2023, Australian international umpiring legend Simon Taufel has completed almost 24 years of elite umpiring and match refereeing.

A former member of the ICC Elite umpires panel, he won a record five consecutive ICC Umpire of the year awards and officiated in 74 Test matches and 174 One Day internationals.

After leaving international umpiring he became the first ICC Umpire Performance and Training Manager.

In the absence of formal longitudinal studies, he has seen an anecdotal increase in the abuse of umpires including some instances of physical contact.

“In Cricket Australia’s stats for last season in the pathways, representative competitions had the highest number of Code of Conduct breaches ever which is a real indicator,” says Taufel.

“We’ve gone from not having a code of conduct 20 years ago to needing one now and captains used to control players and behaviour but they no longer do that,”

“So here we are and I’d say it’s on the increase.”

Despite the rise in breaches, he does not see the need to introduce a red card/yellow card system like football to give more teeth to the Code of Conduct.

“I find those methodologies somewhat inflammatory,” Taufel says.

“and for me education is the answer because I think policing and monitoring of player behaviour is a club issue and shouldn’t belong to the umpires – clubs should be held accountable for the behaviour of their players including removing serial offenders from our sport.”

For Taufel, a holistic approach is the only way to get serious results and he feels focus should taken away from how the match officials deal with bad behaviour and instead placed on prevention though educating the players, captains, coaches, managers and parents:

“It seems the low hanging fruit is to deal with the official and get them to lift their game in managing behaviour, when the real question is – how do we prevent it in the first place?”

Like all sports, cricket faces the challenge of losing umpires from the game and Taufel feels that the number one reason officials get involved is enjoyment of the game and conversely: “the number one reason they walk away, is if they’re not enjoying it.”

Seeking a model to reverse a decline in umpires in grassroots cricket, Taufel tried a new approach in his role as Chairperson of the Highlands Cricket Association in NSW Southern Highlands.

The association had traditionally had difficulty getting club representatives to turn up for the crucial pre-season clubs and captains meeting to address player behaviour.

Taufel tried something different:

“We tried to use a carrot rather than stick where we gave all clubs that turned up a bonus competition three points rather than penalise them for not turning up.”

“I think we need to incentivise education rather than see it as a punishment.”

This collaborative approach is crucial for the long term sustainability of the game according to Taufel: “We’re seeing more competitions in cricket where we need players to officiate themselves – and that’s where most of the real issues happen.”

The need for change and action at the top of the game is crucial to Taufel.

Simon Taufel is now with the Highlands Cricket Association finding ways to increase respect for umpires and reduce the number of matches without an Umpire. Picture: Black Hat Talent

In 2019, The Ethics Centre, led by Simon Longstaff, conducted a review of Australian cricket after the Australian men’s national team were embroiled in the ball tampering scandal in Cape Town.

In the ensuing report, the ninth recommendation was to increase respect for the umpire and according to Taufel: “Cricket Australia has done nothing since 2019 in actually taking on board that recommendation.”

“Officiating is still not in the player education program and the latest red flag is the record number of representative players in breach of the Code of Conduct.”

He sees the lack of respect for authority in wider society as a contributor and sport is a reflection of society as a whole:

“With dropping standards in parenting, the breakdown of the family unit and now no matter who it is – any authority figure including teachers, policemen and of course umpires get constantly challenged,”

“People now feel they have a right to challenge and in cricket that means challenging the umpires which manifests its way down the grades.”

Taufel feels strongly that there is no silver bullet solution and the collective intelligence of the group is always greater than the individual.

In his experience compromise is important, as no single person has the answers or solutions: “It’s always a number of strings that make the rope strong!”

Junior cricketers finding their feet in the Highlands. Picture: Lauren Strode

**

Claire Polosak did not become a cricket umpire through the traditional pathway.

Growing up in Goulburn she didn’t play cricket or remember any girls playing cricket. Her participation in the game was limited to watching Brett Lee and Glenn McGrath on the television and via her family holiday pilgrimage to the Sydney Test match.

At 15 she received a flyer at her boarding school advertising the NSW Umpires and Scorers course, and with support from her father, decided to give it a go.

Her father’s commitment was critical as he would be required to drive his daughter on a 4 hour round trip to the SCG to complete the 6 nights of the course.

She failed the course but continued on with determination.

“I was 15 and had never played cricket so I had trouble seeing the scenarios,” Claire recalls.

“But I’m quite stubborn and I eventually passed and started umpiring in Goulburn during the school holidays.”

When she moved to Sydney in 2008 for her university studies, her umpiring went up a level when she began to officiate in Sydney Premier Cricket and her first women’s international match came seven years later in 2015.

Claire remembers an early battle for respect and recognition as a female umpire.

Turning up on match day, she was sometimes assumed to be the scorer or working in the canteen. But as she worked up the grades she found acceptance once she began to know the players.

“Players will try it on with any new umpire they don’t know and see what they can get away with,” Claire notes.

“Now I don’t think players care what gender the official is, as long as they are making good decisions and being a good communicator.”

From its humble beginnings Claire Polosak’s umpiring career has bloomed.

Claire Polosak speaks about her early battles for respect as a female umpire. Picture: @Cricket NSW

Coming into the 2023/24 season she has now umpired more than 90 international matches including being the first female to officiate in a men’s ODI in 2019 and the first to officiate in a men’s test match as the fourth umpire in 2021.

She is entering the peak stage of her on field career in addition to her off field work with Cricket NSW as an Umpire educator and Female Umpiring lead.

And whilst she has accumulated wisdom over her career, Claire understands that it can only be acquired through time on the field and trial and error: “I wish we could inject 100 games of experience into the arms of new umpires,” Claire says.

“But we’ve all got to learn the hard way, through making errors and over time we find out that umpiring is not suited to everybody.”

The best way forward according to Claire is to set up umpires for success by supporting them.

In her time at Cricket NSW, the umpiring team has had good results in replacing leaving umpires including maintaining a 100% record of providing umpires for Sydney Premier Cricket over the last 10 years.

That success at Premier Cricket level is tempered by an umpiring shortage in regional areas and metropolitan district grassroots competitions in which umpires are more often officiating by themselves without a second umpire or the players umpire their own games.

Although it’s not the only reason, she believes that player behaviour is one of the top reasons why people don’t come back to umpiring: “That’s something that we’re trying to work on – to prepare umpires how to deal with the different scenarios.”

At grassroots level, she feels role modelling of negative player behaviour from the top has an impact: “We know that under 12’s watch cricket on tv and they replicate what they see the top players doing, who in turn are feeling the pressure to perform.”

Cricket NSW working to maintain their 100% record of providing umpires for Sydney Premier Cricket. Picture: Illawarra Cricket Umpires Association

Claire feels there is an irony in the players targeting umpire mistakes: “Umpires are only ever called into the game when a player has made a mistake.”

“I’m basically a Jack in the Box – I won’t come out until either a player speaks to me or I’m required to come out under the laws.”

And she constantly has to remind players that no umpire goes out onto the field of play wanting to make a mistake: “We’re human as well and we’re out there to enjoy the game just like the players.”

Whilst players can make terrible mistakes and often many more in a match than umpires, the reaction to umpires mistakes is very different and they are often a convenient source of blame for player failure.

It’s difficult to imagine players accepting vitriolic abuse if they dropped a sitter or played a woeful shot but the reverse situation is common with umpires.

And when players are forced to umpire themselves, the game takes a different shape.

“When its player umpiring themselves, LBW doesn’t exist. They find out that its harder than it looks.” Claire notes.

As she has risen up through the pathways she has found player disrespect of umpires decreasing, which she attributes to the “prescriptive” Code of Conduct which is very clear in its in application at elite level covering all levels of dissent – covering LBW decisions in which a player looks at their bat in protest or lingers at the crease after the decision.

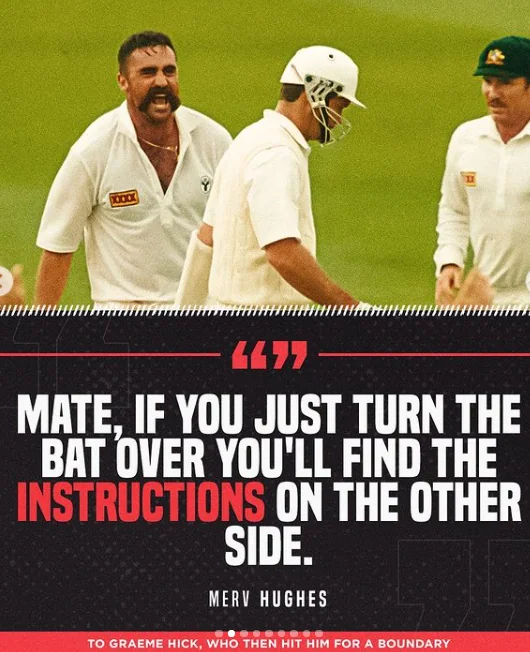

And whilst player vs umpire conflict is generally dissent against a decision, player vs player offers up a different set of adjudication challenges, especially ‘sledging’ or as Steve Waugh termed the practice, the ‘mental disintegration’ of opposing players through constant verbal abuse.

One of cricket’s most mysterious and nebulous concepts is ‘the line’ that players can’t cross – the line where banter crosses into verbal abuse.

Deciding on ‘the line’ takes nuance and it changes from player to player which makes its interpretation complex.

According to Claire there is a first principles rule that anything that constitutes vilification – personal, racial, derogatory is absolutely not allowed.

Deciding what is ‘banter’ and what is ‘verbal abuse’ is open to interpretation and she finds the best results through subtle intervention: “If the opposition are sledging, I’ll check in with the batter to see if it is close to the line,”

“If they want it to stop I’ll pull some reins but there are some batters who thrive on that sort of interaction.”

Although on social media she has seen videos of physical abuse, she has not personally come across any physical assaults of umpires in her time at Cricket NSW:

“There might be some historical videos out there of an umpire being physically threatened but that’s something that’s quite rare and isolated,” she says.

“Generally, cricket respects the tradition and respect is ingrained in the fabric of the game but we are now a lot less patient as a society and I think that can translate to the cricket field.”

Cricket NSW competitions are not played under the provisions of the new addition to Law 42 which allows players to be removed from the field for bad behaviour.

Claire notes: “A lot of competitions in NSW do not use Law 42, so it comes down to the local code of conduct and the way you manage players.”

Another management tool Claire and other umpires use is situation control through the captains – challenging captains to self manage their players and supporters.

The role of the captain is unique in cricket and they have a formal role in player behaviour in line with MCC Law 1.4 which states:

‘The captains are responsible at all times for ensuring that play is conducted within the Spirit of Cricket as well as within the Laws.’

“Captains are integral and are definitely your first port of call in managing a situation,” Claire says.

“If there is frustration building I will use the captain to nip it in the bud with some quiet words and working directly with the captain also increases your presence.”

As cricket embarks on multiple programs to diversify its players, has Cricket NSW kept up with the diversifying of umpires to match the influx of new players, particularly females and the South Asian communities?

“Yes!” Claire says.

“We’ve got a lot of new South Asian umpires which is great and we have seen a strong increase in female umpires – now 20 of our umpires in NSW are female and its growing.” Claire says.

The increase in diverse umpires at the base of the pyramid has led to outcomes at the top.

For the 2023/24 season Cricket Australia announced that seven members of its State and Territory Umpire panels were of South Asian background and six were females who will all have the chance to officiate in various elite competitions.

Other Cricket NSW initiatives to build a strong base of future umpires include the Basil Sellers scholarships who are awarded to the umpiring leaders in their age groups and who complete specialist community officiating workshops.

In turn, the leaders share the knowledge with their peers.

“There’s no downside to more education!” Claire concludes.

Australian cricket’s growing diversity includes a greater representation of umpires from the South Asian community. Sharad Patel (left) Picture: Cricket Australia

**

Whilst umpiring in cricket at the international level is now a high-tech dance of ball tracking technology and player challenges influencing the outcome of decisions, at grassroots level, umpiring the game has remained essentially the same for centuries, with the captains crucial to maintaining the ‘the spirit of the game’ and a code of conduct governing player behaviour that crosses ‘the line’.

Cricket, like all sports has its challenges to meet the needs of a new generation of players and a wider societal trend towards impatience and confrontation of authority means cricket clubs have an important role in managing their own player behaviour instead of leaving it to umpires to play the policing role.

A positive trend towards a healthy future for cricket officiating is the diversification of the demographic base of umpires with significant growth in female and multicultural umpires joining the ranks.

And whilst some players will always look to blame others for their mistakes, it’s fair to say that all grassroots players breathe a sigh of relief and gratitude when a neutral umpire turns up to officiate their game and liberate them from biases and controversies of ‘self umpiring’ and the dilemma of having to give your own teammate out (or not out).

MI’s Suryakumar Yadav tying the shoelaces of SRH’s Rahul Tripathi during a match of Indian Premier League 2023 Picture: instagram @mumbaiindians

Join the Club Respect mailing list

Read Next:

Part 1: Football (Soccer)

Part 2: Rugby League

Part 3: Aussie Rules (AFL)

Part 4: Netball

Part 5: Rugby Union

Part 6: Basketball

Part 7: Cricket

Also by Patrick Skene:

Feature article: Sport’s ugly blind spot – abuse of officials

Patrick is a founder of Cultural Pulse, a leading micro-community marketing and engagement agency that has worked for the past 15 years on sports participation and fan engagement programs for over 100 communities. His recent book ‘The Big O, The Life & Times of Olsen Filipaina‘ has gone into reprint and his stories on the intersection of sport, history and culture have been published by The Guardian Australia, the Age, the Sydney Morning Herald and Inside Sport. He is currently the proud coach of the Rockdale Raiders Under 8B1’s.

Contact Patrick on twitter or LinkedIn