Sport at the crossroads: Basketball's battle against referee abuse

This is Part 6 of our ‘Sport at the crossroads’ series, exploring the way different sports codes and associations are tackling the abuse of officials.

Part 1: Football (Soccer)

Part 2: Rugby League

Part 3: Aussie Rules (AFL)

Part 4: Netball

Part 5: Rugby Union

Part 6: Basketball

Part 7: Cricket

Tales from the frontline tackling the abuse of officials – Basketball

They take their high school basketball seriously in Atlanta, Georgia, in the USA. Too seriously, according to referee Brandon Jack, who has been subjected to sustained abuse, both verbal and physical, from hostile fans, coaches and players that sometimes leads to him requiring an escort to his car after games.

Jack shared one story with Medium.com:

“It was Sunday afternoon and I had just finished officiating a 16U AAU basketball championship game. As I am making my way out the door an angry mum and her son, who just played in the game, approached me to voice their displeasure with how I officiated the game.”

“The player began to threaten me saying, “I’ll beat that refs a**”, while having to be restrained by his mother. I managed to ignore the whole situation and get in my car.”

“However as I was driving away, the mother and son picked up Gatorade bottles and food and threw them at my car.”

Jack was lucky that it did not escalate into the kind of physical violence to referees that became so common that in some US tournaments there are armed security guards, tasked with protecting officials.

“These instances occur all the time where a referee’s safety is in jeopardy by fans who take it to the extreme and fail to realise there is a fine line between passion and flat out abuse.” Jack says.

“Putting on the stripes means you are an authoritative figure in a game environment. However, once you take that shirt off you’re just a regular person and should not have to worry about your life being in danger.”

The increase in danger in taking up the whistle has had an impact according to Jack: “This abusive behaviour from fans and confrontational behaviour by players and coaches is completely unacceptable and a big reason as to why so many officials hang it up after a short stint in the profession.”

“Every time an official puts that shirt on, they’re a target,” Jack adds.

“People believe that we should be perfect and never mess up – we miss calls and get calls wrong and if we do, we’re their personal punching bags and expect us to “just take it.”

**

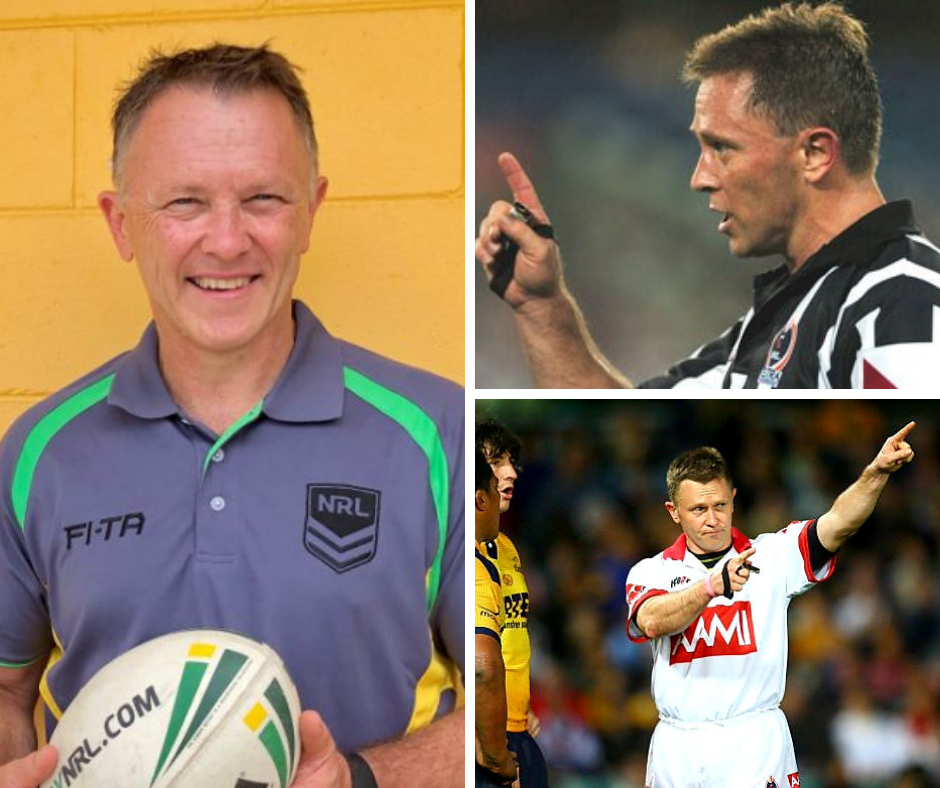

Danger was part of Steve Clark’s celebrated career as an NRL referee. He stared down some of the toughest men in the land in his 15 year career that covered a total of 314 games as a referee and 292 games as the Video referee.

Like Brandon Jack in Atlanta Georgia, Clark was escorted from some games including in a police motorcade from Kogarah to the Harbour Bridge after a rough afternoon at Jubilee Oval and one day police stopping traffic for him to leave Stadium Australia in a car with tinted windows and his brother driving his car for a furtive pick up: “in the back blocks of Silverwater.”

“I’ve had death threats.” says Clark who is freshly returned from a match officials study tour to the US.

“But the violence towards officials there is far worse than we have here and God help us if we ever get to that stage.”

These days Clark has switched sports to Basketball and is the Head of Technical Officials at Basketball NSW – a state-wide portfolio that spans from NBL 1 through to junior leagues and a watching and development of officials at community level.

Although Basketball NSW does not have an issue in attracting new officials, the flow of new recruits is offset by a high churn rate which according to Clark, sits around 34-35% annually.

He feels that a “good 20%” of that churn rate is caused by abuse and he believes the solution lies in coaches improving their behaviour.

“Coming from rugby league where the referee is a long way from the coaches, it really astounds me the levels of abuse that basketball referees cop from coaches.” Clark explains.

“They seem to think that because their proximity to referees is so close that it gives them some sort of right to offer opinions, engage in discussion and sometimes abuse. They feel they have access.”

The intimacy is compounded by the indoor venues that for some nights, Clark feels are “like a high pressure goldfish bowl.” for his referees.

Although there are a number of awareness campaigns on posters and social media like the “No Ref, No play” campaign and others pointing out what a bad look it is to abuse young referees, parents continue to abuse.

Clark’s member protection officer at Basketball NSW will often spend most Monday examining reports, issuing fines, bans and suspensions including bans on parents attending matches.

Legendary NRL referee Steve Clark is now Head of Technical Officials at Basketball NSW. Picture: Basketball NSW

For Clark, the worst parent behaviour comes from an unlikely source – the Under 12 age category.

“The Under 12 parents carry on like their kid is in the NBA and I’ve seen them go ballistic.”

“The kids are out there having a good time with their mates and the parents are ripping into the 14 or 16 year old referee.”

Clark is pretty clear on the reason behind the phenomena: “It’s some parents living their lives through their children and they forget about their responsibilities as adults.”

For Clark, one immediate and controllable step towards improving respect for referees is by improving coach behaviour and their role modelling to players, parents and fans.

“The behaviour comes from the top down and filters through the system and we put a lot of energy into our coaching education.”

“It’s a simple fact that for the game to thrive, coaches have to be the role models, they’re the leaders of the pack, of the club and they set the standard, high or low – they have to be constantly made aware of that.”

“They are the only ones that can tell a parent or a player to be quiet.”

The silver bullet solution for Clark is an old fashioned one – senior mentors who are badged in a governing body polo shirt:

“We need to have more ref coaches available, supporting refs on every court, at every venue and if people are there from head office, in uniform, the bad behaviour tends to stop.”

The eternal vigilance model is preferred by Clark because the behaviour will continue until the deterrents are sufficient: “We had a referee that was manhandled, actually shirt fronted by a coach last year in our top top division in NBL One.”

“He ended up getting a 52 week suspension which a lot of people thought was not enough of a deterrent.”

And has he had to dust off his old rugby league confrontation de-escalation skills?

“Just recently actually when I was in Maitland for a junior league round!”

“I got a message from one of our junior league courts that an over 50 year old guy was sitting in the corner and abusing the 16 year old ref.”

Clark was outfitted in his Basketball NSW uniform and proceeded to sit next to the culprit and asked him to refrain from abusing the referee.

After a lively exchange including Clark offering a free referee course for the offending parent and culminating in a warning that if it happened again, he would be physically removed from the venue.

“He never said another word.” Clark recalls.

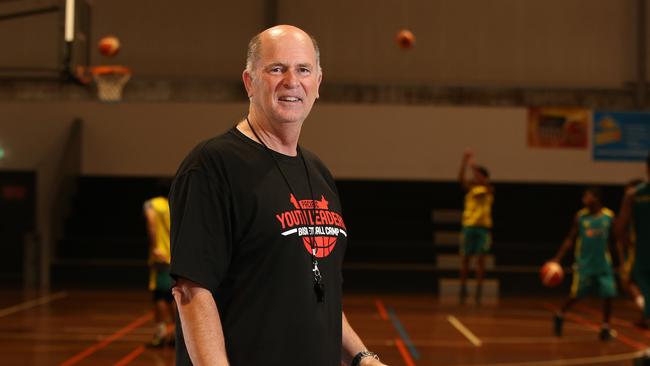

The Silver bullet solution for building resilience in referees, according to Steve Clark, is to have more referee coaches available to support younger referees. Picture: Referee education courses, Newcastle Basketball

**

Overall Clark is positive and happy with the majority of parents and coaches that show respect and gratitude for the match officials and he is pragmatic that it is a problem that will never go away and can only be managed down: “Being brutally honest, I don’t think we’ll ever eradicate it but we can significantly reduce it through support and education and equipping them to deal with it.”

“But we in Australia are ahead of a lot of places in development and education, and all the issues are the same across the world, it’s just the depth of the problem.”

His study trip to the USA helped him develop renewed gratitude for the overall NSW basketball refereeing landscape:

“Our referees are committed and dedicated and we are proud of our record of never having lost a game due to a shortage of referees.”

He has had few close shaves that have threatened Basketball NSW’ proud record: “It’s a juggling act and we know that some referees do more games than they probably physically should.”

“It would be really good if we can get more people.”

And his formula for refereeing success: “Quite simple!”

“Professionalism starts in attention to detail whenever you go out on court. Then you can enjoy yourself,”

“And respect not only your refereeing colleagues but players, coaches, the sport and most importantly your own role.”

A terrifying incident in Oklahoma. Former NBL referee Jon Chapman says “God help us if we (Australia) ever get to that stage.”

Respect was something referee Toni Caldwell had to earn the hard way in her journey to the top of the NBL and for a lonely 10 year stint, she was the only female referee in the elite Australian competition.

Starting in Ipswich she worked through the pathways as a pioneer to achieve a career tally of 157 NBL games over a 13 year career, leaving a legacy of inspiration for aspiring young female referees to pick up the whistle.

She originally played the game but when her height topped out at 5’3” she decided she could have more impact with the whistle, entering a world of comparatively towering giants.

Toni was tested early when someone reached through the window of the referees room and grabbed her aggressively which she found “shocking!”

She also had to deal with some fixed mindsets which created some barriers including a couple of older coaches who didn’t think she should be out there and questioned her understanding of the physicality of the men’s game.

Her response to them was always the same: “I just referee by the rulebook and it’s the same set of rules for men and women.”

As she moved through the pathways she realised the value of support: “You have to be tough and resilient but it is important to have support both from within the game and people outside it.”

Another factor that seemed to work in Toni’s favour was she was late to the game, starting at 18 with her serious career happening in her mid to late twenties.

“I had a bit more life experience and I could communicate with my career in media as a journalist and had developed emotional intelligence which is important for a referee.” Toni explains.

“And most importantly I wasn’t verbally abused at the age of 15-16 and I probably would have walked away in disgust.”

In her first NBL game it was one of the NBL’s legendary players and coaches who gave her an enduring memory of support: “I was nervous and will never forget Phil Smyth grabbing me’”

“He said ‘Toni don’t listen to a word they way, it’s all bullshit and you’ll be great!”

NBL Legend Phil Smyth was very encouraging for Toni Caldwell’s first NBL game. Picture: Scott Fletcher

Overall her experience and rapport with coaches and players was positive: “I was always happy to talk, communicate and listen.”

Her problem lay with negative fan behaviour which ranged from getting called ‘Barbie’ to receiving a lot to threatening posts on social media.

“I actually wouldn’t log into social media during the NBL season, I had to change my online name and lock down my accounts.” she explains.

“No one realises the abuse referees receive due to the fans having direct access and its appalling.”

She feels there is an unwritten code of silence that still governs abuse of referees:

“Referees aren’t meant to speak about these things and its seen as a weakness for an official to say how they are feeling which makes the job a lot harder for this generation of elite referees.”

For Toni the situation is worse at grassroots level with its combination of social media abuse, coach abuse and the close proximity of parents and coaches to the referees.

“Trust me, the elite level is so much easier than the grassroots level and I don’t know how we have so many officials or how we keep these kids.”

After retiring from the NBL, Toni is the President of Ipswich Basketball in South Queensland and doubles up as the Association’s referee coordinator with about 50 referees in her stable.

She has witnessed parental, coach and player abuse first hand and has dealt with the impact on referees mental health.

“The abuse that happens in Associations makes me not want to be there – it’s terrible what grownups say to abuse these young officials.”

According to Toni Caldwell, referee abuse is having an impact on mental health. Picture: Joey Guidone (ESPN)

Her most troublesome age bracket correlates with Steve Clark’s experience at Basketball NSW – the Under 12’s.

“I’ve lost track of how many times I have to say to parents on a Sunday: “they’re kids, they’re learning, it’s Under 12’s.”

“We had massive issues at the last U12 state championships with parents abusing officials.”

Toni observed the impact first hand when she spoke to a young referee who was preparing for the upcoming Under 12 state championships and whose main concern was a coach yelling at him.

She advised him that if he was unacceptably abused by a coach to “throw the coach out, the sun will shine tomorrow and its part of growing as an official.”

“But they shouldn’t have to do it at Under 12 level and they know you can’t play state championships without referees – we’re crucial to the event happening.”

Toni is unsure of the specific cause of the antisocial behaviour of parents at junior basketball games: “I don’t know whether it’s because the parents are new, or whether they see it at higher levels but I just don’t understand why or how grown ups think it’s ok to abuse a kid.”

“It’s a blind spot because if a parent said the same thing to a 14 year old player there would be a complaint straight away by other parents but the same duty of care does not apply to a 14 year old referee.”

The Under-12 age category, according to both Steve Clark from Basketball NSW and Toni Caldwell from Ipswich Association is the worst age group for parents and coach abuse.

Another issue for Toni is the dismissive attitude coaches, parents and fans have to referees, treating them like ‘the other’ and not as community members providing an essential service:

“We’re going out there because we love the game and people forget that we’re not going out there to ruin the game for anybody,”

“We’re human and often totally different people off the court.”

Despite the PR and awareness campaigns calling for their shared humanity to be taken into consideration by coaches and parents, the abuse continues and strict deterrents have to be enforced to prevent chaos.

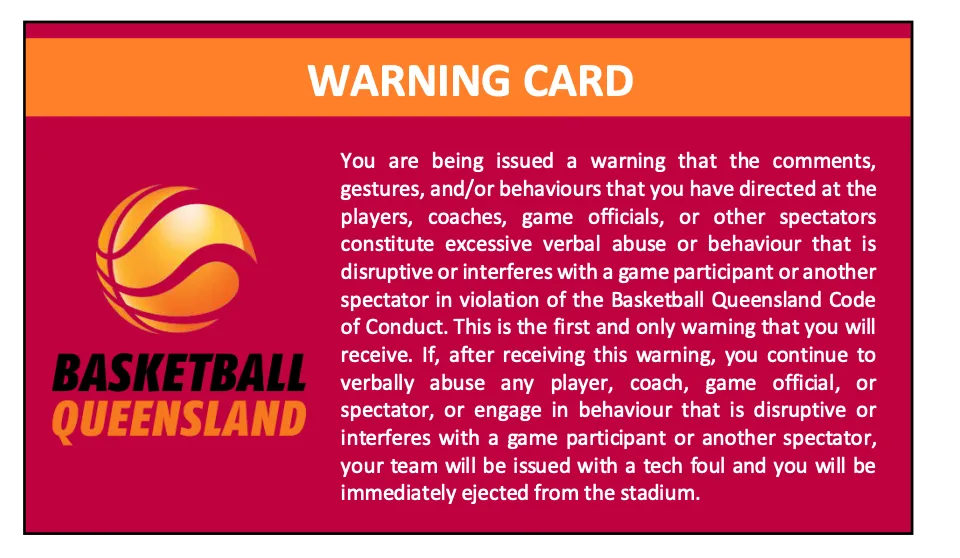

In Queensland, parents can now receive a warning card and then a tech foul which is added to the parent’s child’s team fouls.

With their off-court behaviour now impacting on the court, parents are now increasingly being ejected from games for abuse.

Basketball Queensland have implemented a range of initiatives to curb parent abuse, including a Warning Card system.

Looking forward, Toni can see some drastic ‘lockout’ style measures at some venues: “Have no parents or spectators. That would fix it. As an adult you should never speak to a child like that, no matter what the environment. Ever!”

“Kids mimic these behaviours and you don’t see these behaviours anywhere else, so let’s eliminate their access, you have no automatic right to abuse kids.”

Each parent entering a building to watch basketball should comply with a simple mantra according to Toni:

“We only accept verbal encouragement of the kids when they are playing and if you can’t control yourself from abusing the referee, stay out of the building, go and have a coffee.

Witnessing first hand the strength and confidence to referee grow in the next generation of females inspires Toni: “How amazing are these kids who are 12, 13, 14 years old and who choose to referee.”

“They inspire me everyday and I don’t think I could have jumped on a court at their age and took control of a game and dealt with the criticism they do from adults.”

For Toni the path to improved respect for officials starts at the Association level: “Associations need to employ more full time refereeing mentors to provide support and have a courtside experienced presence.”

Along with support mentors, Toni feels the greatest gap is investment in education for players, coaches and parents in which a greater understanding of the game would reduce abuse:

“In Ipswich I ran a referee course on the rules for our rep coaches and I was amazed at how many of them didn’t know simple rules – only two had read the rule book.”

The ignorance of the basics of the game was a transforming moment for Toni: “I was amazed firstly, how they were coaching kids and secondly how they thought they could ever question a referee on the rules if they didn’t know them.”

When Toni moved to Cairns and took up a role in refereeing there, she decided to build empathy at the ground floor: “We made it a rule that all U14 and U16 rep players had to do a beginner referee course and if they wanted to be part of a rep team they had to referee 3 games. The impact was instant.”

Reflecting on her journey, Toni Caldwell is thrilled to see the next generation of female referees come through: “I didn’t have many female role models above me and I always prided myself on being there for younger officials.”

“That’s what kept me in the game for so long, being there and supporting them no matter what.”

Pioneer Referee Toni Caldwell Refereed 157 games over 13 years as an NBL referee. Picture: NBL

For former NBL Referee Jon Chapman, the most abusive court for a young referee to step onto was not the Under 12’s but the domestic senior competitions like the over 35’s on a Thursday night.

“It’s the dads with football backgrounds playing some basketball in their later years,” Chapman explains.

“You’re a green teenager trying to wrangle a court full of competitive men, many with a poor understanding of the game – and the abuse is direct abuse, you’re literally 2 metres away from them and you’re an easy target.”

According to Former NBL referee Jon Chapman, the toughest group to officiate are the Over-35s because “you’re an easy target”. Picture: City of Stirling

His 6 years and 120 games refereeing in the NBL provided him with some insights into human nature and trade-offs that referees have to make according to the situation.

Fan and coach abuse is more acceptable and digestible at elite refereeing level according to Chapman: “I reckon once you get to that level, the abuse is defined quite differently than if you’re a local official or in the feeder competitions.”

“At the elite level you treat it as part of the entertainment product – it’s part of the show and the occasional thing we might hear from the crowd – it’s best to treat it as part of the product.”

Although he developed a thick skin, it’s still jarring when he receives abuse that includes his name: “I’ve never been fearful of my life or family but it’s still strange when people yell out your name when they abuse you, like they know you.”

Like a lot of his peers, Chapman began refereeing early at 12 in an association in Melbourne:- “it was more attractive than flipping burgers.” he recalls.

He worked his way up through the pathways to reach the elite level and like Toni Caldwell and Steve Clark, he believes the most effective method to reduce abuse is the presence of someone senior: “like a supervisor or a senior/known referee. The physical presence with age and status is helpful and it just helps to dampen some of it.”

Referees in training wear a green shirt. Picture: Bunbury Basketball Association

He has seen it all at junior level with parents consistently abusing referees and is a supporter of zero tolerance: “In Under 10’s, little Johnny is stumbling around with a basketball trying to learn and in what should be the most positive atmosphere, all of a sudden ugly parent syndrome kicks in.”

Chapman feels there is a lack of accountability for actions that needs to be remedied: “I think it’s too easy for a parent to run their mouth without some sort of checking – keep it simple and warn them, then ban them from the ground.”

“Those parents don’t read the posters – as soon as you pass the kiosk, it’s game on and a 15 year old kid with a whistle is an easy target for a mob of parents.”

According to Jon Chapman there are trade-offs that referees have to make according to the situation, such as treating referee abuse at elite level “as part of the entertainment product.” Picture: Michael Klein

The most pragmatic solution according to Chapman is “Peer monitoring.”

“It works best when fellow parents tell them to calm down or the coaches turn around and let them know that their behaviour is not acceptable.”

The situation has moved beyond cautions and follow up emails after games according to Chapman: “It should literally be ‘You’re removed’ and the game doesn’t start until you go and and the team has to suffer because of the parents.”

Chapman ardently believes this approach would work: “Watch how parents start championing peer monitoring when Little Susie can’t resume her game or loses a match because of points deduction – connect parents and spectators to the health of their team’s ability to play.”

“That’s where this has to land – penalise the team if the parents are directly impacting the development environment, maybe a foul or maybe the captain gets yellow carded.”

Chapman also believes that the coach has a major role to play in setting the tone of what parents are allowed to do.

“You look at inexperienced parents at local level – they will use the coach’s reaction to things as a barometer of what they should be doing. An animated coach often leads to animated parent groups.”

He feels there is no shortage of positive role models: “There are some awesome coaches who do take it upon themselves to set the tone of standards for player and parent behaviour. This behaviour should be rewarded and incentivized.”

For Jon Chapman the best solution for reducing parent abuse is “peer monitoring”, in which behaviour is self-regulated to avoid the team being punished. Picture: OK3Sports

Chapman joined Steve Clark on the National Officiating Summit study tour to the USA and beyond noting the unacceptable levels of violence, referee shortages and cancelled competitions, he discover a key difference between Australia and American grassroots officiating.

“The notion of litigation against match officials is huge which increases the pressure on officials to leave and more pressure on the ones that stay.” Chapman explains.

“Filing lawsuits is a normal part of American life and over there referees get blamed for a range of things – from their kid injuring themselves slipping over on an unwiped basketball court to a ref’s decisions ‘costing’ their kid a crack at college ball because of a bad call.”

He was stunned to learn that officials have their own private indemnity insurance to counter claims of being sued.

“It’s a tool of the trade over there. It will happen here one day and I don’t think associations are ready for lawsuits against a referee, for example, who ‘allowed’ a game to be too physical that led to injuries.”

“We’re lucky it hasn’t happened here yet.”

Join the Club Respect mailing list

Read Next:

Part 1: Football (Soccer)

Part 2: Rugby League

Part 3: Aussie Rules (AFL)

Part 4: Netball

Part 5: Rugby Union

Part 6: Basketball

Part 7: Cricket

Also by Patrick Skene:

Feature article: Sport’s ugly blind spot – abuse of officials

Patrick is a founder of Cultural Pulse, a leading micro-community marketing and engagement agency that has worked for the past 15 years on sports participation and fan engagement programs for over 100 communities. His recent book ‘The Big O, The Life & Times of Olsen Filipaina‘ has gone into reprint and his stories on the intersection of sport, history and culture have been published by The Guardian Australia, the Age, the Sydney Morning Herald and Inside Sport. He is currently the proud coach of the Rockdale Raiders Under 8B1’s.

Contact Patrick on twitter or LinkedIn